The Influencing Machine

George Soros, the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art, and how one man remade Eastern European culture with this one weird trick

It’s a meta-NGO, with many layers and systems that overlap and interlock. We’re talking about internet systems, lobbying organizations, think tanks, coercive philanthropy, media networks, cultural networks, university networks, and, of course, art worlds. It’s the convergence of a religious movement, a multi-level marketing pyramid scheme, a machine-learning model. It is very political and it is definitely aspirational. Let’s call it “The Influencing Machine.”

-Aaron Moulton, The Influencing Machine

[This isn’t really a book review but I’m going to treat it like one for the purposes of shilling Aaron Moulton’s The Influencing Machine1 (Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw 2022), 205 pages, which you can (and should) buy here.]

My last post was about conspiracy theories and the problem of dismissing the ideas that get labeled as conspiracy theories out of hand. For one thing, conspiracy theories can often teach us something about the world even when they are wrong. But conspiracy theories, or stories about the world that look uncannily like conspiracy theories, often turn out to be real, and if you are reflexively dismissive of these narratives because you find them dangerous or déclassé or self-evidently wrong, you will end up with blind spots that will make the world make a lot less sense.2

What if I told you, for example, that after the Cold War a powerful network of ideological operatives, all directly under the control of George Soros, launched a campaign to reprogram the cultural identity of the former Soviet Union? What if I told you that under the guise of promoting “artistic freedom,” Soros and his sprawling supranational network of nested NGOs and private enterprises, spun a web of well-funded art centers across twenty nations, each acting as a propaganda outpost with the explicit intent to dismantle national traditions and reprogram these societies for globalist integration, relying on handpicked artists, theorists, gallerists, museum curators, and bureaucrats to do so, all in an effort to prime the populace of these newly liberated nations into accepting a program of political and economic “shock therapy” that would reconstitute these societies from within? And finally, what if I told you, that having successfully done all of that, once the program was (formally) shut down in the early 2000s, the world would just kind of forget that it ever happened?

This might sound an awful lot like a conspiracy theory, and yet, it’s all entirely and indisputably true.

i. Aaron Moulton uncovers a sprawling supranational network of coordinated cultural influencers all working at the behest of George Soros over the course of a decade to remake the societies of Eastern Europe. No, seriously.

I first encountered the art critic and researcher Aaron Moulton in early 2023 through an obscure podcast called Verdurin hosted by the academic Pierre d'Alancaisez. Until the recommendation algo dropped this podcast in my lap, I had never heard of Aaron Moulton. I had never heard of Verdurin, and I had never heard of Pierre d'Alancaisez. I had also never heard of the subject of their conversation, The Influencing Machine, Moulton’s just then released book and art project chronicling the too-on-the-nose-to-be-true story of George Soros and the Soros Center for Contemporary Art (SCCA), which through its emphasis on “socially engaged practice,” single-handedly reshaped the art world across post-Soviet Europe.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Neither Moulton nor d’Alancaisez could be described as right-wing, and both seemed almost hesitant—apologetic, even—about the material Moulton had uncovered during his research. They repeatedly reassured listeners—all several dozen of us—that they were fully aware of the “anti-Semitic tropes” their discussion might inadvertently bump up against. Moulton devotes an entire section of his book, pointedly titled “The Boogeyman,” to exploring the difficulty of speaking plainly about George Soros’s vast influence.

In that section he cites the ADL’s position on the matter:

A person who promotes a Soros conspiracy theory may not intend to promulgate antisemitism. But Soros’ Jewish identity is so well-known that in many cases it is hard not to infer that meaning. This is especially true when Soros-related conspiracy theories include other well-worn antisemitic tropes such as control of the media or banks; references to undermining societies or destabilizing countries; or language that hearkens back to the medieval blood libels and the characterization of Jews as evil, demonic, or agents of the antichrist.

Even if no antisemitic insinuation is intended, casting a Jewish individual as a puppet master who manipulates national events for malign purposes has the effect of mainstreaming antisemitic tropes and giving support, however unwitting, to bona fide antisemites and extremists who disseminate these ideas knowingly and with malice.

When it comes to investigating Soros, the ADL might just as well write: “This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here.”

So what is a well-intentioned researcher to do when confronted with the efforts of the SCCA, an openly coordinated, well-documented campaign to reshape the cultural foundations of over twenty nations, backed by an immensely powerful individual, the mere utterance of whose name can cast an art critic in good-standing into the outer darkness?

Most people, understandably, choose not to talk about it at all. Aaron Moulton, to his lasting credit, chose to write a book about it and make it the center of years of his life’s work.

Here, in summary, is what he uncovered:

The Soros Centers for Contemporary Art (SCCA) were established in over twenty cities across the former Eastern Bloc beginning in the early 1990s, operating under the umbrella of the Open Society Institute (OSI). These centers, according to Moulton and the hundreds of primary sources he consulted while writing his book, were not simply neutral spaces for promoting artistic freedom but were carefully engineered ideological instruments, designed to guide newly “liberated” societies away from their existing cultural identities and toward a Western liberal-democratic model.

Moulton characterizes the SCCA network as “a case study in the paradox of free will and determinism,” where art was not organically produced but steered, curated, and conditioned by institutional mechanisms that rewarded ideological compliance and punished deviation. Each center adhered to a standardized set of protocols laid out in the SCCA Procedures Manual—referred to by insiders as “the Bible” or “the Talmud”—which dictated everything from grant distribution and exhibition themes to the classification of artistic practices according to pre-defined, Western-oriented art-world jargon.

…this manual included guidelines on human resources and other office-culture rituals such as hiring, staff salaries, business plans, what office equipment to buy, how to make an expense report, and how to write a rejection letter. It gave detailed instructions on how to create the SCCA Archive, which was an essential aspect of the stated purpose of the SCCA Network. Within this archiving system there is even a comprehensive vocabulary for labeling art according to materials and themes… This vocabulary of keywords and tags, as well as other systems that the SCCA used to innovate and institutionalize visual culture to produce what Octavian Esanu3 refers to as “SorosArt.”

What the SCCAs promoted above all was “socially engaged practice”—a term that sounds relatively innocuous but functioned as a gatekeeping ideology, privileging identity-based, anti-nationalist, and politically progressive art and artists. The SCCAs had operating budgets that often dwarfed those of the ministries of culture in the host countries, effectively making them the sole arbiters of what contemporary art was and who got to participate in it. In Moldova, for example, the SCCA invented the very concept of contemporary art as it would come to be institutionally understood, and which came to dominate the national art scene.

Artists who adopted the preferred themes and methods—especially those addressing gender, minority rights, migration, and EU integration, etc.—were vaulted into international recognition, while artists working in traditional media or engaged with national culture were systematically excluded. As Irina Cirois, the director of the SCCA in Bucharest put it, “The SCCA reduced the number of those who were seen as legitimate artists to a very small number… In reality the SCCA, the avant-garde of the open society, was paradoxically an elite club.”

“Socially engaged practice” neatly dovetailed with the application of “coercive philanthropy,” a term first coined to describe the work of the Ford Foundation but perhaps nowhere is more evident than in the practices of the SCCA. Briefly, coercive philanthropy is a type of selective cultural funding that appears neutral on its face but is intended to shape ideological outcomes under the guise of benevolence. According to Moulton, the SCCAs succeeded at institutionalizing this approach, offering grants and opportunities only to those artists whose work aligned with Open Society’s political and cultural goals. Rather than overt censorship, the mechanism was subtler: by rewarding the right kind of art, the network marginalized dissent without needing to suppress it directly. Open calls appeared democratic, but the criteria for inclusion—often framed in the language of progressivism, and “Human Rights” liberalism—functioned as ideological filters.4 In this system, artists were not told what to make, but through a carefully designed architecture of incentives understood what kinds of projects would be approved, published, and exhibited. Over time, the SCCAs became what art researcher Lioudmila Voropai called “monopolists of the cultural-political markets.” Under these conditions, more organic artistic expressions were not silenced so much as made institutionally irrelevant.

Moulton’s research draws on dozens of interviews with former SCCA directors, curators, collaborators, and OSI officials. He documents the emergence of a new class of curator-bureaucrats, many of them in their twenties and thirties, often with no prior curatorial experience, who were recruited by the SCCA’s Executive Director Suzanne Mészöly5 —please make sure to read the footnote—to operate as on-the-ground cultural engineers. These individuals were supplied with budgets, institutional support, and international legitimacy that made them, in effect, sovereign over their local art scenes, though entirely beholden to the interests and demands of OSI and its extended network. Through annual exhibitions and grant-making, the SCCAs did not just shape the discourse—they were the discourse, creating what Serbian art historian Miško Šuvaković later dubbed “Soros Realism.” The centers redefined the role of both curator and artist, not as meaning-makers but as participants in a system of managed perception.

Moulton says of these exhibitions:

Much of the language of exhibition-making coming out of the Network is very unique to this story: herculean bureaucratic tactics; reimagining public space; using sacred, out-of-context venues; reframing the exhibition as an exclusive site of cultural production; treating the artist as medium; and unifying artistic practices. And, as we’ll see, unifying art worlds. Each of these turns would manifest in an unprecedented way through the Annual Exhibitions, and would thereafter be virally synchronized across the entire network. It was like a force of nature.

Maybe most disturbingly, the entire operation has been essentially memory-holed. Despite its scale and success, the history of the SCCA network has received almost no attention in mainstream art history or critical theory (the SCCA doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page). Major institutions and scholars who were involved at the time have omitted their participation from public-facing records; archives are missing or unavailable; and those who might speak about it have often refused. In short, the SCCA network didn’t just fund art. It redefined—or really, produced from scratch—the artistic culture of an entire region of the world, not just in the aesthetics it promoted but in the structures of legitimacy and influence it installed—transforming the post-Soviet cultural landscape in a way that continues to shape how art is made, funded, and understood across much of Europe and beyond—and it did so in a way that made its own operations nearly invisible to history.

ii. Why this matters, and what we might take from this curious recent episode of cultural history

The legacy of the SCCA is a bit hard to track and is mostly opaque. The SCCA as an organizing body formally dissolved in the early 2000s, but has left behind a few successor entities scattered across the Eastern Bloc in places like Slovenia and Romania, while most of the centers were quietly shuttered. Meanwhile, many of the curators, directors, and artists cultivated by the network now occupy leading roles in contemporary art institutions and academic programs throughout Europe and the United States. A Google search of the names of the early participants reveals a still very active and deeply embedded roster of cultural scene-makers, all more or less still committed to the same meta-politics of Western-liberalization.

It’s hard to assess the importance and impact of this kind of program, but it is at least non-negligible and you can assume that someone like Soros would only spend this kind of money because he thought it mattered. It reveals, if nothing else, that culture can be manufactured from above—and that aesthetics, intellectual currents, and even moral frameworks can be shaped not through censorship or brute force, but through the strategic distribution of resources.

The SCCA exposes the machinery behind what often appears to be spontaneous cultural development. It shows that what gets framed as “authentic” or “emergent” is frequently the result of logistically managed, ideologically filtered incentives, imposed not by the state or “the market” but by unelected networks of scene-makers operating under the banner of philanthropy.

Of course, the same tactics—coercive philanthropy, perception management, the use of artistic institutions as vectors for ideological enforcement—have become dominant within American cultural life as well. It has always been thus. In the decades following World War II, the CIA famously infiltrated the Western art world, operating through organizations like the Congress for Cultural Freedom and with the help of front groups such as the Ford Foundation, actively promoting Abstract Expressionism as a cultural counterweight to Soviet Realism. Frances Stonor Saunders carefully details these efforts in his book Who Paid the Piper? The Cultural Cold War, and connects the dots on how Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others became ideological assets in a battle over the moral superiority of Western liberalism. The public story was one of spontaneous genius and aesthetic freedom. The reality, as in the case of the SCCA, was far more orchestrated.

Today, major museums, art schools, and funding bodies in the U.S. operate with ideological guardrails that closely resemble those put in place by the SCCA and one is forgiven for wondering how much of these practices are direct descendants of previous cultural engineering schemes. Grants require diversity statements. Exhibition proposals must align with values of “equity,” “decolonization,” or “social justice.” Failure to conform doesn’t result in censorship—it simply means exclusion from the institutional economy. The use of art as a soft-power instrument is now openly acknowledged, often lauded, and embedded in the institutional DNA of contemporary cultural production. What gets funded, what gets shown, what gets written about, sold, memetically reproduced… all of it. It’s all carefully managed.

Recognizing this flow of resources, ideology, and artistic expression, doesn’t require believing in shadowy cabals or omnipotent puppet-masters. In fact, what makes the SCCA story so compelling—and so unsettling—is how brazen it is. There was no secrecy, no deep cover, no encrypted memos. The network was an open conspiracy. The documents were published, the procedures outlined, the funding sources acknowledged. It’s just that no one really cared. It was operating in plain sight, its effects normalized through repetition and institutional authority. That, in a way, is the lesson: if you want to see where power resides in culture, don’t look for what’s hidden. Look for what’s everywhere.

iii. Personal coda

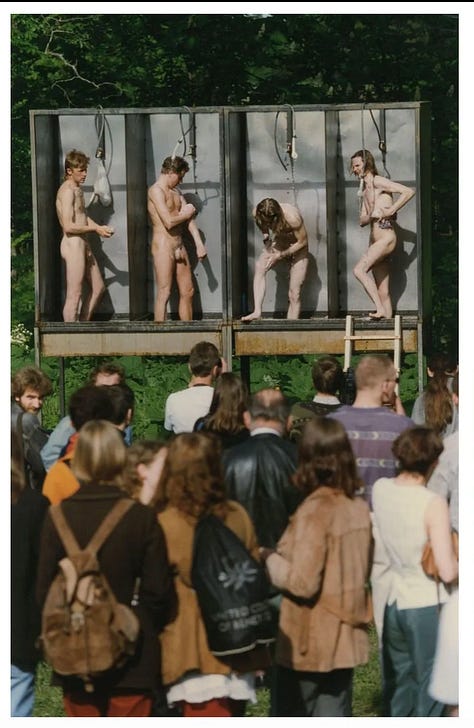

I have to confess I’m still not entirely sure what to make of all this. When I first heard the podcast, then read Moulton’s book, and followed up with some of my own research into this strange and largely forgotten chapter of recent history, it felt like my suspicions about George Soros and his malignant influence had been confirmed. Much of the art itself struck me as deliberately perverse—bad in the specific way so much contemporary art is bad, reveling in transgression for its own sake—and it was easy to see how such work might function as a softening agent, preparing a population for the more disorienting and atomizing effects of Soros-style liberalism.

But there is another potential story to be told here. I could easily recast the sinister, conspiratorial vision of the SCCA that began this post in a far more sympathetic light. It might go something like this:

What if I told you that after the Cold War, George Soros funded a network of contemporary art centers across twenty countries in the former Soviet bloc to promote artistic freedom? These Soros Centers for Contemporary Art provided much needed infrastructure, training, and international exposure to artists in countries where state-sponsored art had long been rigid and ideologically constrained by Soviet repression. Working with local curators and cultural workers, the SCCAs introduced new ideas, media, and global conversations to regions that had been isolated from the world and from their native traditions for generations. Their goal wasn’t to erase national identities but to offer platforms for creative engagement during a time of immense social transition. Once local institutions matured, the SCCAs quietly shut down, leaving behind a generation of artists fully equipped to sustain a local culture freed from the yoke of their communist past.

Do I believe this version? No, not really. It’s at least as naive as the first version is cynical. And anyway the precise motivations are not really the point. Soros has done a lot of damage to the world and there’s absolutely no reason to soft-peddle the extent of it. But this more sympathetic version does help me understand something about why modern political and cultural life seems unable to escape his grasp, and why, when we look around, we see him everywhere.

Soros so often “wins” not because of secret plans, but because he understands the basic mechanics of power and its relationship to meaning. To the question of why, he might tell himself a story of benevolence, where we might see his villainy, but to the question of what and how the story is the same either way: George Soros shows up. He sees a vacuum and he fills it. He funds infrastructure where none exists. He staffs it with personnel who share his beliefs at the highest levels of abstraction and he lets them do whatever they are going to do.

If others want to contest the vision he promotes, they would do well to start by taking culture as seriously as he does—not as decoration or critique, but as both the precursor to power and as power’s favorite tool for amplification. If the history of the SCCA teaches us anything, it is that culture is not merely reflective of society; it produces it. And those who build its institutions shape the world we come to see as real.

It’s a really good book with a lot of fascinating detail not covered in this post like George Soros’ intimate relationship to Esperanto, as well as some really interesting formatting and design features, plus a back section with about 80 pages of glossy art photos.

On the other hand, if you accept conspiracy theories too uncritically, without any discernment for what is real versus what is fake, what is directionally true but technically incorrect, or what is technically correct but is directionally untrue, you will also suffer from blind spots and the world will make a lot less sense but for other reasons. As always, be careful out there.

Esanu began his career was the first curator for the SCCA in Moldova in 1996.

Mandatory diversity statements serve a similar function. They are not, on their own, ideological litmus tests, but effectively guarantee ideological conformity.

One of the weirdest details of this whole story is that after the SCCA dissolved, Mészöly disappeared from the art world seemingly without a trace, despite her position of outsized importance, only to reappear years later as a “Vibrational Healer” on a Pleasantville, New York public access show called The Listening Place. Utterly surreal.

The Dean of the Yale School of Art had this on her resume:

https://news.yale.edu/2016/02/09/renowned-curator-marta-kuzma-named-dean-yale-school-art